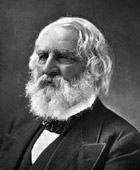

HENRY WADSWORTH LONGFELLOW, whom Griswold describes as the greatest American poet, was born at Portland, Maine, February 27, 1807, and he died at Cambridge, Massachusetts, March 24, 1882.

His father was of Puritan stock, and a lawyer by profession. He possessed the necessary wealth to give his children school opportunities.

At the age of fourteen young Longfellow was sent to Bowdoin College, where he graduated at eighteen. He was a close student, as shown by the testimony of his classmate, the talented Nathaniel Hawthorne, also by the recollections of Mr. Packard, one of his teachers. These glimpses that we catch of the boy reveal a modest, refined, manly youth, devoted to study, of great personal charm, and gentle manners. It is the boy that the older man suggested. To look back upon him is to trace the broad and clear and beautiful river far up the green meadows to the limpid rill. His poetic taste and faculty were already apparent, and it is related that a version of an ode of Horace which he wrote in his Sophomore year so impressed one of the members of the examining board that when afterward a chair of modern languages was established in the college, he proposed as its incumbent the young Sophomore whose fluent verse he remembered.

Before his name was suggested for the position of professor of modern languages at Bowdoin, he had studied law for a short time in his father's office. The position was gladly accepted, for the young poet seemed more at home in letters than in law. That he might be better prepared for his work he studied and traveled in Europe for three and one-half years. For the purpose of becoming acquainted more thoroughly with the manners and literature of other countries, he visited France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Holland, and England. Returning home in 1829 he entered upon his duties at Bowdoin, where he remained for six years. Upon the death of Mr. George Ticknor, in 1835, Longfellow was appointed to the chair of modern languages in that eminent seat of learning. Again sailing for Europe he visited the Scandinavian countries, Germany and Switzerland. On this visit he became acquainted with the literature of northern Europe. Again returning to the United States, he entered upon his duties at Harvard. This position he held for nineteen years when he resigned, and was succeeded by James Russell Lowell. Thus, for twenty-five years, from 1829 to 1854, he was a college professor in addition to his ceaseless literary work.

At a very early age Longfellow gave evidences of poetic genius. Numerous stories are told of his childish effusions. From the commencement of his collegiate course it became evident to his teachers and fellow-students that literature would be his profession. While a youth his poems and criticisms, contributed to periodicals, attracted general attention. Hawthorne speaks of him as having scattered some delicate verses to the wind while yet in college. Among those youthful poems we may mention, "An April Day," a finished work that shows all of the author's flowing melody in later years.

In 1833 he published a translation of the Spanish verses called "Coplas de Manrique," which he accompanied with an essay upon Spanish poetry. This seems to have been his first studied effort and it showed wonderful grace and skill.

The genius of the poet steadily and beautifully developed, flowering according to its nature. The most urbane and sympathetic of men, never aggressive, nor vehement, nor self-asserting, he was yet thoroughly independent, and the individuality of his genius held its tranquil way as surely as the river Charles, whose placid beauty he so often sang, wound through the meadows calm and free. When Longfellow came to Cambridge, the impulse of transcendentalism in New England was deeply affecting scholarship and literature. It was represented by the most original of American thinkers and the typical American scholar, Emerson, and its elevating, purifying, and emancipating influences are memorable in our moral and intellectual history. Longfellow lived in the very heart of the movement. Its leaders were his cherished friends. He too was a scholar and a devoted student of German literature, who had drank deeply also of the romance of German life. Indeed, his first important works stimulated the taste for German studies and the enjoyment of its literature more than any other impulse in this country. But he remained without the charmed transcendental circle, serene and friendly and attractive. There are those whose career was wholly moulded by the intellectual revival of that time. But Longfellow was untouched by it, except as his sympathies were attracted by the vigor and purity of its influence. His tastes, his interests, his activities, his career, would have been the same had that great light never shone. If he had been the ductile, echoing, imitative nature that the more ardent disciples of the faith supposed him to be, he would have been absorbed and swept away by the flood. But he was as untouched by it as Charles Lamb by the wars of Napoleon.

From this period poems and essays and romances flowed from his inspired pen in almost endless profusion. In 1835 appeared "Outre Mer," being sketches of travel beyond the Atlantic; in 1839, "Hyperion, a Romance," which instantly became popular. In the same year with "Hyperion," came the "Voices of the Night," a volume of poems which contained the "Coplas de Manrique" and the translations, with a selection from the verses of the "Literary Gazette," which the author playfully reclaims, in a note, from their vagabond and precarious existence in the corners of newspapers--gathering his children from wandering in lanes and alleys, and introducing them decorously to the world. A few later poems were added and these, with the "Hyperion," showed a new and distinctive literary talent. In both of these volumes there is the purity of spirit, the elegance of form, the romantic tone, the airy grace, which were already associated with Longfellow's name. But there are other qualities. The boy of nineteen, the poet of Bowdoin, has become the scholar and traveler. The teeming hours, the ample opportunities of youth have not been neglected or squandered, but, like a golden-banded bee, humming as he sails, the young poet has drained all the flowers of literature of their nectar, and has built for himself a hive of sweetness. More than this he had proved in his own experience the truth of Irving's tender remark, that an early sorrow is often the truest benediction for the poet. At least two of the poems in "voices," "Psalm of Life," and "Footsteps of Angels," penetrated the common heart at once, and have held it ever since. A young Scotchman saw them reprinted in some paper or magazine, and meeting a literary lady in London, he repeated them to her, and then to a literary assembly at her house; and the presence of a new poet was at once acknowledged. "The Psalm of Life" was the very heart-beat of the American conscience, and the "Footsteps of Angels" was a hymn of the fond yearning of every loving heart. Nothing finer could be written. They illustrate the fact that our inner consciousness breathes the air of immortality just as naturally as our lungs draw in the air of heaven.

In 1841 appeared "Ballads, and Other Poems;" in 1842, "Poems on Slavery;" in 1843, "The Spanish Student," a tragedy; in 1845, "Poets and Poetry of Europe;" 1846, "The Belfry of Bruges;" 1847, "Evangeline;" 1849, "Kavanaugh," a prose tale; in the same year, "The Seaside and the Fireside," a series of short poems; 1851, "The Golden Legend," a mediaeval story in irregular rhyme; 1855, "The Song of Hiawatha," an Indian tale; 1858, the "Courtship of Miles Standish;" 1863, "Flower de Luce;" 1867, a translation of Dante; 1872, "The Divine Tragedy," a sacred but not successful drama; in the same year, "Three Books of Songs;" 1874, "Hanging of the Crane;" 1875, "The Masque of Pandora;" and 1878, "Keramos." The above gives an outline of his literary work, though he wrote numerous poems not mentioned, and made some excellent translations.

Among his short poems that have gone into every day literature, and are known in every home, may be mentioned "The Building of the Ship," "The Old Clock on the Stairs," "The Bridge," "The Builders," "The Day is Done," "The Ride of Paul Revere," "The Evening Star," "The Snow Flakes," "Excelsior," "Psalm of Life," and "Footsteps of Angels." Where can we find a more popular collection than that given above? Eminently, Longfellow is the poet of the domestic affections. He is the poet of the household, of the fireside, of the universal home feeling. The infinite tenderness and patience, the patios and the beauty of daily life, of familiar emotion, and the common scene,--these are the significance of that verse whose beautiful and simple melody, softly murmuring for more than forty years, made the singer the most widely beloved of living men.

In 1868 he visited Europe for the third time. What a contrast between this and former visits! Cambridge University conferred upon him the degree of LL. D., and Oxford that of D. C. L. The Russian Academy of Science elected him a member, and he was also made a member of the Spanish Academy. He was received everywhere with marks of distinction. His fame had reached even the poor classes and the servants of nobility. It was known that he would visit the queen on a certain day, and as he passed along the streets and corridors leading to her reception room, he was surprised to see the number of persons looking from doors and peeping from windows to see him. The queen received him most cordially. She told him the persons he had noticed were her servants, that they had learned to love him, and that the poet who could thus command the affections of the poor and humble, as well as of the rich and great, surely wears a greater than an earthly crown. And why not love him? He is the poet, above all others, who has swept every chord of tenderness, beauty, and pathos; and he has lightened the sorrows and heightened the joys of every home. His poems are apples of gold in pictures of silver. The gentle influence of his poetry is sweetly and unconsciously expressed in one of his own poems:

Come read to me some poem,

Some simple and heart-felt lay,

That shall soothe this restless feeling,

And banish the thoughts of day.

Not from the grand old masters,

Not from the bard sublime,

Whose distant footsteps echo

Through the corridors of Time.

* * * *

Such songs have power to quiet

The restless pulse of care,

And come like the benediction

That follows after prayer.

Other fields were open for his muse, but with a steady and unerring purpose he held his pen close to the domestic heart. Scotland sings and glows in the verse of Burns, but the affections of the whole world shine in the verse of Longfellow.

A genial writer has paid our favorite a deserved compliment. He says that "in no other conspicuous figure in literary history are the man and the poet more indissolubly blended than in Longfellow. The poet was the man and the man was the poet. What he was to the stranger reading in distant lands, by

`The long wash of Australasian seas,'

that he was to his most intimate friends. His life and his character were perfectly reflected in his books. There is no purity, or grace, or feeling, or spotless charm in his verse which did not belong to the man. There was never an explanation to be offered for him, no allowance was necessary for the eccentricity, or grotesqueness, or willfulness, or humor of genius. Simple, modest, frank, manly, he was the good citizen, the self-respecting gentleman, the symmetrical man."

For a long time he lived at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a house once occupied by General Washington as his headquarters; the highway running by his gate and dividing the smooth grass and modest green terrace about the house from the fields and meadows that sloped gently to the placid Charles, and the low range of distant hills that made the horizon. Through the little gate passed an endless procession of pilgrims of every degree and from every country to pay homage to their American friend. Every morning came the letters of those who could not come in person, and with infinite urbanity and sympathy and patience the master of the house received them all, and his gracious hospitality but deepened the admiration and affection of the guests. His nearer friends sometimes remonstrated at his sweet courtesy to such annoying "devastators of the day." But to an urgent complaint of his endless favor to a flagrant offender, Longfellow only answered, good-humoredly, "If I did not speak kindly to him, there is not a man in the world who would." On the day that he was taken ill, six days only before his death, three school-boys came out from Boston on their Saturday holiday to ask his autograph. The benign lover of children welcomed them heartily, showed them a hundred interesting things in his house, then wrote his name for them and for the last time.

Few men had known deeper sorrow--his first wife having died in Holland, in 1835; his second wife having been burned to death in 1861, by her clothes taking fire, accidentally, while she was playing with the children. But no man ever mounted upon his sorrow more surely to higher things. His song and its pure and imperishable melody is the song of the lark in the morning of our literature.

"Type of the wise who soar but never roam,

True to the kindred points of heaven and home,"

Biography from: http://www.2020site.org/poetry/index.html |