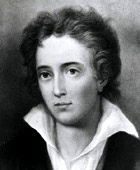

PEROY BYSSHE SHELLEY was born at Field Place, near Horsham, in Sussex, August 4, 1792; and his eventful life came suddenly to a sad termination. He had gone out in a boat to Leghorn to welcome Leigh Hunt to Italy, and while returning on the eighth of July, 1822, the boat sank in the Bay of Spezia, and all on board perished. When his body floated to shore a volume of Keats' poetry was found open in Shelley's coat pocket. The remains were reduced to ashes and deposited in the Protestant burial ground at Rome, near those of a child he had lost in that city.

His father was a member of the House of Commons. The family line could be traced back to one of the followers of William of Normandy. Thus in noble blood Shelley was more fortunate than most of his brother poets, considering the estimate that England placed upon the distinction of caste. He had all the advantages of wealth and rank, and hence much was expected of him.

At the age of ten Shelley was placed in the public school of Sion House, but the harsh treatment of instructors and school-fellows rendered his life most unpleasant. Such treatment might have been called out by his fondness for wild romances and his devotion to reading instead of more solid school work. While very young he wrote two novels, "Zastrozzi" and "St. Irvyne, or the Rosicrucian," works of some merit. Shelley was next sent to Eton, where his sensitive nature was again deeply wounded by ill usage. He finally revolted against all authority, and this disposition manifested itself strongly in Eton.

Shelley next went to Oxford, but he studied irregularly, except in his peculiar views, where he seemed to be constant in his thought and speculations. At the age of fifteen, he wrote two short romances, threw off various political effusions, and published a volume of political rhymes entitled "Posthumous Poems of My Aunt Margaret Nicholson," the said Margaret being the unhappy maniac who attempted to stab George III. He also issued a syllabus of Hume's "Essays," and at the same time challenged the authorities of Oxford to a public discussion of the subject. He was only seventeen at the time. In company with Mr. Hogg, a fellow-student, he composed a treatise entitled "The Necessity of Atheism." For this publication, both of the heterodox students were expelled from the college in 1811. Mr. Hogg removed to York, while Shelley went to London, where he still received support from his family.

His expulsion from Oxford led also to an inexcusable confusion in his social life. He had become strongly attached to Miss Grove, an accomplished young lady, but after he was driven from college her father prohibited communication between them. He next became strongly attached to Miss Harriet Westbrook, a beautiful lady of sixteen, but of social position inferior to his. An elopement soon followed, and a marriage in August, 1811. Shelley's father was so enraged at this act that he cut off his son's allowance. "An uncle, Captain Pilfold--one of Nelson's captains at the Nile and Trafalgar--generously supplied the youthful pair with money, and they lived for some time in Cumberland, where Shelley made the acquaintance of Southey, Wordsworth, De Quincey and Wilson. His literary ambition must have been excited by this intercourse; but he suddenly departed for Dublin, whence he again removed to the Isle of Man, and afterward to Wales. After they had been married three years and two children were born to them they separated. In March, 1814, Shelley was married a second time to Harriet Westbrook, the ceremony taking place in St. George's Church, Hanover Square. Unfortunately, about this time the poet became enamored of the daughter of Mr. Godwin, a young lady who could `feel poetry and understand philosophy,' which he thought his wife was incapable of, and Harriet refusing to agree to a separation, Shelley, at the end of July in the same year, left England in the company of Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin."

Upon his return to London, it was found that by the deed, the fee-simple of the Shelley estate would pass to the poet upon his father's death. Accordingly he was enabled to raise money with which he purchased an annuity from his father. He again repaired to the continent in 1816, when he met Lord Byron at Lake Geneva. Later he returned to England and settled at Great Marlow, in Buckinghamshire. His unfortunate wife committed suicide by drowning herself in the Serpentine River in December, 1816, and Shelley married Miss Godwin a few weeks afterward (December 30).

Leaving his unfortunate social career, we come now to consider his poetical works. At the age of eighteen he wrote "Queen Mab," a poem containing passages of great power and melody. In 1818 he produced "Alastor, or the Spirit of Solitude," full of almost unexcelled descriptive passages; also the "Revolt of Islam." Shelley was most earnest in his attentions to the poor. A severe spell of sickness was brought on by visiting the poor cottages in winter. Poor health induced him to go to Italy, accordingly on the twelfth of March, 1818, he left England forever.

In 1819 appeared "Rosalind and Helen," and "The Council," a tragedy dedicated to Leigh Hunt. "As an effort of intellectual strength and an embodiment of human passion it may challenge a comparison with any dramatic work since Otway, and is incomparably the best of the poet's productions." In 1821 was published "Prometheus Unbound," which he had written while resident in Rome. "This poem," he says, "was chiefly written upon the mountainous ruins of the Baths of Caracalla, among the flowery glades and thickets of odoriferous blossoming trees, which are extended in ever-winding labyrinths upon its immense platforms and dizzy arches suspended in the air. The bright blue sky of Rome, and the effect of the vigorous awakening of spring in that divinest climate, and the new life with which it drenches the spirits even to inspiration, were the inspiration of this drama." Shelley also produced "Hellas," "The Witch of Atlas," "Adonais," "Epipsychidion," and several short works with scenes translated from Calderon and the "Faust of Goethe." These closed his literary labors, for he died as described in the beginning of this sketch, in 1822.

A complete edition of "Shelley's Poetical Works" with notes by his widow was published in four volumes in 1839, and the same lady gave to the world two volumes of his prose "Essays," "Letters from Abroad," "Translations and Fragments." Shelley's was a dream of romance--a tale of mystery and grief. That he was sincere in his opinions and benevolent in his intentions is now undoubted. He looked upon the world with the eyes of a visionary bent on unattainable schemes of intellectual excellence and supremacy. His delusion led to misery and made him, for a time, unjust to others. It alienated him from his family and friends, blasted his prospects in life, and distempered all his views and opinions. It is probable that, had he lived to a riper age, he might have modified some of those extreme speculative and pernicious tenets, and we have no doubt that he would have risen into a purer atmosphere of poetical imagination.

The troubled and stormy dawn was fast yielding to the calm noonday brightness. He had worn out some of his fierce antipathies and morbid affections; a happy domestic circle was gathered around him, and the refined simplicity of his tastes and habits, joined to wider and juster views of human life, would imperceptibly have given a new tone to his thoughts and studies. The splendor of his lyrical verse--so full, rich and melodious--and the grandeur of some of his conceptions, stamp him a great poet. His influence on the succession of English poets since his time has been inferior only to that of Wordsworth. Macaulay doubted whether any modern poet possessed in an equal degree the "highest qualities of the great ancient masters." His diction is singularly classical and imposing in sound and structure. He was a close student of the Greek and Italian poets. The descriptive passages in "Alastor" and the river-voyage at the conclusion of the "Revolt of Islam," are among the most finished of his productions. His better genius leads him to the pure waters and the depth of forest shades, which none of his contemporaries knew so well how to describe. Some of the minor poems, "The Cloud," "The Skylark," etc., are imbued with a fine lyrical and poetic spirit.

THE CLOUD.

I bring fresh showers for the thirsting flowers,

From the seas and the streams;

I bear light shade for the leaves when laid

In their noonday dreams.

From my wings are shaken the dews that waken

The sweet birds every one,

When rocked to rest on their mother's breast,

As she dances about the sun,

I wield the flail of the lashing hail,

And whiten the green plains under;

And then again I dissolve it in rain,

And laugh as I pass in thunder.

Biography from: http://www.2020site.org/poetry/index.html |