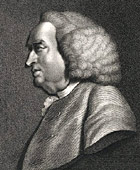

Johnson, Samuel, one of England's most noted men of letters. He was born in Litchfield in 1709. He entered Pembroke College, Oxford, with a reputation for prodigious learning, but he was compelled by poverty to leave before taking a degree. His father was a bookseller, and Samuel was a great reader. He taught in a grammar school. He married a widow twice his own age and spent her little fortune of $4,000 in trying to establish a school of his own. Garrick, the actor, was one of his pupils. In 1737 Johnson moved to London and starved for years, trying to earn a living by writing. He wrote articles for magazines and Tory comments on the proceedings of Parliament.

He was a man of huge, unwieldy form, rolling gait, slovenly habits, and far from pleasing table manners. An inherited tendency to scrofula, which affected him from his birth, had impaired his eyesight, distorted his features, and was accountable for the deep melancholy which took possession of him and doubtless for many if not most of his peculiarities. He monopolized conversation, bore down all opposition, and antagonized people recklessly. Goldsmith used to say, "There is no getting on with Johnson. If his pistol misses fire, he knocks you down with the butt of it." He came to London unknown, unbefriended, ragged, untidy; he often walked its streets at night because he was too poor to procure a lodging; he lunched on coarse food because he was penniless; and yet by sheer ability Johnson rose gradually but surely to a recognized dictatorship in a literary world that included such writers as Fox, Gibbon, Burke, and Goldsmith. His services as a political writer, and not as a man of letters, secured him finally a government pension of $1,500 a year, after which he was more comfortable. Before this, he was at times so poor in purse that he was obliged to make his calls of business and otherwise on "clean shirt day," the only day in the week on which he could afford clean linen. Neither he nor his wife seems to have had the slightest ability to make one shilling do the work of two. In 1755 he completed his celebrated Dictionary, but the entire amount he recieved for it had been drawn and spent before he finished the work.

Of his writings Rasselas is the most popular. The scene is laid in Abyssinia and Egypt, but deals with the never-ending search for happiness. "Answer, thou great Father of Waters," says one of the searchers, addressing the Nile, "Tell me if thou waterest throuh all thy course a single habitation from which thou dost not hear the murmurs of complaint." It was written in a week's time to pay the funeral expenses of his mother.

His Dictionary, already mentioned, is now out of date, but it is a monumental work. It is of first importance as the earliest noted work of the kind in English. It is the forerunner of the dictionaries since published on both sides of the Atlantic. Some of his definitions are so bigoted, not to say spiteful, as to be humorous. That on oats is famous: "Oats, a grain which, in England, is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people." An offended Scot retorted by inquiring where the learned lexicographer could find such horses as were produced in England or such men as were reared in Scotland.

Other of Dr. Johnson's works are important. The Idler and The Rambler were serious, solemn imitations of the sparkling Spectator.

His Lives of the Poets, a series of biographies, are still read, but only by the student of literature. Johnson's style is dignified and sonorous. He was given to using long words. "His hand is heavy. His step is heavy, but not blundering; his blows are as strong and deft as those of a lion; his voice, loud, but sonorous. His words roll at times like the sound of distant thunder, but they never fall in a light shower. Whether his opinions be agreeable or not, they are couched in dignified language."

Johnson's Life by James Boswell is considered the greatest biography ever written. It runs through several volumes, but is excellent reading. Boswell's reputation rests wholly on this work, and it is safe to say that Dr. Johnson, despite his great learning, would be known little more than Roger Bacon were it not for his biographer.

Mrs. Johnson died in 1752. Johnson lived for many years in bachelor quarters, but with a room ready for him whenever he chose to occupy it at the home of a Mr. Thrale, a wealthy brewer. In this home he spent much of his time for many years. Mrs. Thrale, a vain but warmhearted woman, surrounded him wim comfort and nursed him tenderly in illness. After Mr. Thrale's death the lady made a foolish second marriage which gave Johnson offense, and this home was closed to him. He had at this time a house in Fleet Street. Here he maintained for years several impecunious persons who quarreled outrageously with each other and made their benefactor miserable. Johnson, however, endured it with patience because he pitied them. However quick he may have been to resent an injury or insult from a superior, he was unfailingly kind to inferiors and generous to the poor. Johnson was for many years the center of a literary club, by whom he was regarded with great affection. In 1784 he died at his lodgings alone, in so far as he was without relatives, but he was attended by affectionate friends. The horror of death which had haunted him throughout his life left him toward the last and he died in great peace. He was buried fittingly in Westminster Abbey. |